I like running, I like exercising, I love, love, love soccer. I've been away from soccer for a long time, and for many reasons related to the sport, I just can't go back. I used to want to be a professional, you know, so I was on my way to a professional career, but I quit. When I started training, I had anemia, so I couldn't train with the other girls. I literally had no strength, so I mostly stayed on the bench. And at that time, I wouldn't have been able to be "so-and-so," you know, play women's soccer. I couldn't play with the girls, not at all. With the boys, I always felt very comfortable, but with the girls, I didn't. Then I quit because I transitioned and all that, and after that, there was no way for me to play soccer. To this day, I haven't seen a trans guy... And I'm too old to play soccer. If I were 18, I would absolutely keep going, really, I would pursue a soccer career in every way possible. But I'm turning 27, so no way.

The soccer scene is very conservative and very sexist, and they would definitely have an issue with trans men. They already have issues with trans people in sports. I saw something recently about a law concerning trans people in the Olympics. Because the treatment of trans women is different from that of trans men in sports. It's more acceptable for a trans man to compete. A trans woman is seen as superior to cis women because of testosterone. Because people think testosterone is the be-all and end-all. Because of all these so-called "biological" factors, as if trans people weren’t biological. And then there's all this controversy about trans bodies in sports. In soccer, it's a huge taboo. Women's soccer is already a taboo in Brazil, imagine a trans person in soccer. There was even a news story about a trans guy who hasn’t undergone hormone therapy or anything. He's on the Brazilian women's futsal team, and he hasn't transitioned, hasn't changed his name or anything because he's a professional soccer player. His career is in women's futsal, and if he transitions, he’ll lose his career.

For trans men, it's easier to enter sports because we don’t naturally produce high levels of testosterone. We produce testosterone at a low level, and when a trans man undergoes hormone therapy, his testosterone levels are regulated to match those of a cis man. For health reasons, you can’t exceed that level. But for trans women, they naturally produce more testosterone than estrogen, and for cis society, testosterone seems to make all the difference. It's "what makes a man a man," you know, "it defines a man." So, trans women are not seen as women because they produce testosterone, and they face all these challenges. Like Tiffany, who was a volleyball player for SESI Osasco and is now playing for the Brazilian team. She was accepted, but then there was all this controversy about wanting to kick her out because she played well, and the media kept saying, "Oh, because she's a trans woman, she’s much stronger," which isn’t true, you know. It’s just pure prejudice. Simple as that. The only difference is that she's a trans woman and the others are cis women. It’s not about hormones, it's not about strength. Her hormone levels are the same as a cis woman’s. If they weren’t, it would be a doping issue. So it’s pure prejudice. They try to use biology as an excuse for their prejudice. And the "Cystem"—with a C—will continue. Because the standard is cis; if you deviate from that, it’s seen as a disorder.

Nazism used to try to justify its "antics" with biology, you know, absurd claims. The same way they tried to prove white supremacy over Black people based on a distorted reading of Darwinism, from a misinterpretation of Darwin’s theories. They read it that way and believed it. And they used this to justify their beastly thoughts, their prejudices. Like how women weren’t allowed to vote in the past—people used their prejudices to say, "women can’t vote." The same thing happens to us. It’s pure ignorance. It’s just prejudice to use biological terminology to justify your biases. You have the right to express yourself, but you don’t have the right to invade, oppress, or interfere in other people’s lives, in how they live.

For my thesis, I decided to divide it into two parts: studying the Black diaspora and Black people in Brazil. And the issue of gender and sexuality in these bodies. Like, we live with so many layers. Black people haven’t had the same opportunities as white people, so you start looking at intersections of class, race, and gender. And you see that at every level, every stage, people don’t have the same conditions as others. And this has resulted in countless issues. So I wanted to study that. How is the Black body perceived? How is the Black gay trans body perceived? Is it desired? Are people willing to date this body? Today, we know that trans people, trans bodies—especially trans women, and many of them Black trans women—we have data on how trans women leave home at 13 years old, how they have a higher mortality rate. But trans women aren’t undesired, you see. It’s part of the cis culture of "women to marry vs. women who aren’t marriage material." The Black body isn’t seen as marriage material. Black women’s bodies, the violence they suffer, the loneliness of Black women. Black women aren’t undesired. It’s white women for marriage, and Black women for dating, for sex, and that’s it. There are studies, data—this is real.

So when a trans woman, especially one who fits a conventional beauty standard, thin and all, she could, I don’t know, be on the cover of Vogue today. Because, like it or not, there’s a cut-off point there. But a Black trans woman who doesn’t fit the Vogue beauty standard, who doesn’t look like a cis person, will never be on the cover of Vogue. Not anytime soon. I’m not trying to compare trans people’s struggles, I’m not trying to pit us against each other. That’s not it. But I’m saying these differences exist because of the systemic intersections of gender, race, and class. This cis system, where the white man is at the top of the power hierarchy. And this affects everyone—white women, Black women. That’s why I said white women’s feminism is different from Black women’s feminism. While white women were fighting for the right to work, Black women were already working. It was like... "Wait, we’re already working, we don’t need that, we need to fight to be paid fairly, to have our work valued, to have opportunities, just like white women had the opportunity to study, we want that too."

Some of the readings I’ve done include accounts from travelers describing what people were like, how they behaved, but it’s always from the traveler’s perspective. There are records of women being with women, men being with men, people who were men dressed as women, who were seen as sorcerers and respected in some tribes under different names. Just from those accounts, you can see that Black bodies existed and behaved in different ways. But we don’t know much because so much was erased. What I want to do one day, if I have the opportunity to pursue a PhD, is go after those primary sources, go after records to study how Black people saw themselves, how they perceived their bodies. But not from a foreign perspective. Trying to understand from within that culture, from a diasporic lens.

In my childhood, I played a lot of soccer and rode my bike—I was quite the little rascal. My parents let me play freely. They gave me dolls but didn’t push it, so they bought me what I wanted, like "I want a little man"—I used to call action figures "little men." I played a lot with my neighbor in the back, played soccer, ran around—everything a cis boy was supposed to do, I did. It was a peaceful childhood, but when it came to clothing, it was always difficult. I remember that I didn’t like "feminine" clothes, the ones meant for girls, only "masculine" ones. That doesn’t mean my parents knew "ah, he’s trans," because I was just a kid—and there are many trans people who played with dolls, wore pink, and are trans, you know? I’m not saying this was a defining factor, but I’m talking about my childhood: the things that were read as for cis boys, I used, played with, wanted, and thought were cooler.

In my adolescence, since I grew up in a religious family—my parents are Jehovah’s Witnesses—I started attending religious services and wearing dresses. I hated wearing dresses and skirts, but I wore them because it was only for religious gatherings, and I had to do those things. But I HATED putting on those clothes. So much so that I bought long skirts and tall boots to make myself more comfortable, always in black—things that made me feel less uncomfortable. But ugh, I hated it because it felt like I had to be like the women there, you know… I thought the men’s suits were so beautiful, I wanted to wear those suits, and I had to wear a dress… Like, that wasn’t my thing. Anyway, I didn’t last long there (laughs). I was a Jehovah’s Witness until I was 16 or 17.

In my teenage years, my chest started to grow, and that began to bother me. Up until then, I hadn’t cared about my body or my weight—I ate everything, played sports, so I was never focused on it. But then I stopped playing soccer, got into religion, got my period, and my body started to change. My chest grew, and suddenly, I didn’t like anything about these changes. I went through a period of depression in high school. To get out of that depression, I started exercising, walking every day, running. And after I left religion, a huge weight lifted off my shoulders.

Then, I got into UFRGS. Going to university, leaving home, stepping out of my small-town bubble—it was everything to me. I’m even scared of what could have happened if I had stayed in that Novo Hamburgo bubble. I think my life would have been so boring. I think about how much I discovered, how much I got out of my bubble, how much I learned about politics, about society, about how we live and behave. That all happened at university. Of course, I learned things in my course, but university opened doors to everything—a new culture, an experience of exchanging ideas with people, young people my age who were also discovering things, sexuality, everything. After I got into university, wow, I met a whole new range of people, and it was wonderful, it was amazing, the exchange was excellent, it was everything good. Go to university—it’s really worth it (laughs).

From my adolescence, when I left religion and gained more autonomy over my body, over what I wanted to do with my hair, about myself… I started feeling happier, allowing myself more, because I was doing what I wanted, what made me feel good. So my sexuality flowed more… Ah, it flowed, flowed—really flowed (laughs)—yes, I left religion, came out as a lesbian, and started being with women. Aaaahhh, what a joy (laughs). Then I allowed myself more, I was with men, but I never had the desire, the interest, or the will to go further with men. Today, I only date women—but I won’t say "never" because I might end up drowning. Gemini, right? (laughs). Wow! I cut my hair—I remember when I cut my hair in college—it was really, really, really good! It felt amazing when I started wearing clothes I saw as masculine, dress shirts and all, but when I cut my hair, wow, a new me was born. It was excellent. It was wonderful!

And at university, I found myself as a trans man.

Because I was always searching, always allowing myself… It was like I was wearing layers of clothing and slowly taking them off on a really hot day. So I kept taking them off, taking them off. Allowing myself, allowing myself, allowing myself… Until I finally allowed myself to be what I had always been repressing. And then, I spent two years in therapy because I didn’t accept being trans, I didn’t accept being a trans man at all. I thought, "I’m not like those cis men out there," you know? I was like, "No, that’s not me," and I was really angry about it. But at the same time, not allowing myself to be me was harming my health. That’s when I understood that I am a man. A Black trans man!

But my mental health… I remember 2016 was a really rough time. From the middle of the year to the end of 2016, I got really bad, fell into deep depression, it was really tough. Everything that was already bad got worse—my struggle with self-acceptance. Everything that was already terrible became unbearable, because I was already depressed from not accepting myself. I thought about suicide and everything, I was put under home hospitalization. Then I thought, "I think I need to allow myself, because otherwise, I won’t live, I won’t be able to keep going. Either I allow myself or I die." Those were the two options.

I thought: before trying to kill myself, I should give myself a chance, allow myself. I remember it was a morning, I left early, went to the health center and said, "Ma’am, I’m going to kill myself, so I need to stay here," you know? And she took me in, "What’s going on with you?" And I explained, "Look, I’m feeling really bad, really depressed, and I came here asking for help so I don’t do something." They referred me to the mental health center (CAPS). They called, and my brother came to get me. After that, I was treated at CAPS, with a psychiatrist and psychologist there. I was in home hospitalization and on medication. It was a horrible week—I had so many anxiety attacks, so many panic attacks. To this day, I don’t know how I got out of that hole. I have no idea. Like, things just kept moving forward, and suddenly, I was out… Because at that point, I had no perception of dreams, no perception of life, no perspective on anything at all. That was my last chance. I woke up that morning and thought, "Wow, I’ll give myself one last chance. Either I kill myself or I go to the clinic." And it turned out to be the right choice, because I’m still here. I made a good decision. Then I started therapy, got support from friends and family, but mostly from my friends—a lot. I was always with my friends, and it was really, really good, because those were the moments I felt happy, that I could share. Because when I was with family, I kept the secret, but with my friends, I could be open.

After I came out to my friends and then to my family, everything became lighter, lighter. Once I allowed myself, everything started to flow again, everything got better. Then I started living as Morgan, and I wanted to live again. Life started to have meaning and importance for my BEING.

It was something that was always inside me, but I didn't know what it was. I always knew there was something, and later, as I allowed myself more freedom—when I could be with women, which was something I wanted but didn’t know I wanted—I felt that thing inside me. In therapy, I kept denying it because I didn’t want to be that man. But then, as I allowed myself more, I realized: man, I’m not that man, you know? I’m not a cis man. I’m a trans man, first and foremost. I will never be a cis man because I am not a cis man. I’m already coming from a place where I won’t reproduce even half of what they do, you know? Me, with the knowledge I’ve gained, with my awareness of society—what I have and what I want to have.

But it’s also hard because accepting yourself as a trans person… Damn, the fear of being trans. I slowly started accepting myself, and it was a gradual process of understanding—like, I really am a trans man, and I have to take pride in that part of me. But it wasn’t like, "Oh, I’m trans, and I’m proud," super quickly. It was a process. And, like, it was a process for my family, for everyone around me, and still is. Later, I realized that life itself is a process, and I started expanding my understanding of society. I also started understanding what it means to be a man, what it means to be a woman, and how all these meanings were constructed onto bodies—what it means to be a man, what it means to be a woman.

I began to understand bodies more, how there’s a system that reads them and imposes how you’re supposed to act. I realized this when I saw that other peoples, in other places, read bodies differently. My African ancestors—I don’t know exactly where I’m from, but from the African continent—each tribe, each place, saw bodies in a different way. Not in this colonial way. Man, I also spent a good while studying radical feminism because I thought, "That makes sense, gender is constructed, yeah, for sure." I was even with a girl who was a radical feminist. And we had a lot of discussions about this, always talking. But I always kept thinking, "Man, what I feel inside goes beyond what you can explain. What I feel, you can’t explain." And that was the turning point, the peak moment. Damn, I need to live my truth because your theory doesn’t include my body, you know? And then I thought, man, I’m going to live my life, do my thing.

Then I started realizing that society is plural, that there are many ways of living, many perspectives, and that many standards have been imposed on many bodies, on everything. And I calmed down—"Damn, I’m not that guy," you know? When you study masculinities, you start seeing, for example, how Black men’s bodies are objectified.

Today, we’re more socially open than we were years ago. So now I can say I’m non-binary. Man, back in the ‘80s? No way. "What is that?" Even if you felt like, "Damn, this doesn’t fit me." But then the radical feminists come in saying, "You’re just leaving one box to enter another." Like, I’m not creating categories. I’m just saying that bodies are free. And people will always interpret bodies because we live in society. Now, whether you impose a category is another issue—if you do, then yeah, you’re setting up a prejudice against it.

And like, no, I want to wear pink too, you know? I want to wear blue, and I’m still going to be Morgan. Wearing flip-flops. But I feel more comfortable in this body. "Oh, but you’re trans, you want to be a man." Dude, I am a trans man. I will never be a cis man. I, Morgan. I identify this way. I identify as a trans man. I have many issues, just like everyone has issues. Man, we’re not atoms, you know? You’re not going to deconstruct everything. You’re not an atom. And then people use arguments they don’t even understand to justify things… We live in society. Just respect people’s bodies.

The very act of objectifying and trying to justify things through a System is already a pattern, you know? And it’s just more of the same. A cis pattern. "Oh, but there’s no such thing as cis and trans." Okay, but you’re using a cis argument to fuel your prejudice. So go ahead, de-objectify yourself completely and live like numbers, then. Done. (laughs) And it’s also this strong desire to go back to something… Man, society has already advanced. You need to see where we are today. People want to go back to something that exploded with the Big Bang. "This is the truth," and you want to impose your truth because your truth is already a standard. The idea of not having a standard is already a standard. So, like, you’ll get stuck in an endless loop, an endless spiral. Like, "not having a standard of having a standard," you know? There will always be a standard. (laughs)

When I realized it, I thought, "Damn, I’m a man." I wasn’t even thinking about the distinction between "trans" and "cis," you know? I was just like, "I’m a man, and now I have to shave and hold the door open for my girlfriend." These little things. I didn’t want that toxic behavior, I didn’t want to reproduce it—I wasn’t that, and I rejected all of it. Out of anger, a lot of anger, towards "that" man. Because gender was constructed too. So I had a lot of discussions about what gender was with my therapist. She was studying transmasculinities, and she helped me a lot. She didn’t tell me, "Morgan, you are this." I searched for myself until I found the me that I am today. She just talked to me. And that’s the role of a psychologist—to help you find your own path.

It’s also about the phallus, right? Having a penis. Because having a penis or a vagina is the main thing that fuels prejudice, that fuels radical feminism—whether you have a pussy or a dick. And I was like, "Man, I don’t have a dick." And then I realized I’m a trans man, and I thought, "Damn, that’s beautiful—I’m an evolution of the species." (laughs) I can get pregnant, I can do whatever I want. And I also discovered this because, when you have a vagina, I think, you end up being seen as inferior to a cis man. Because he has a dick, and you have a vagina—so he is superior to you. I am a trans man, and I have a vagina. And that’s the deal. If you want to be with me, that’s how it is. I’m not going to hide myself just to be loved by someone. I’m not going to stop being me now because some girl doesn’t want to be with me.

I closed myself off from relationships. My body was never desired, I always had very low self-esteem, and I always felt unwanted for being, at the time, a Black lesbian woman. And then I thought, "I'll become a trans man and also..." So I learned to live with loneliness, you know? And I also learned to like loneliness. I learned to live in a way that loneliness helped me love myself first. Which is the first step to having self-esteem, right? Loving yourself. To be able to love someone else. So, in my case, through loneliness itself, I learned to love myself. Man, I want to be happy. I want my happiness first. I'm not going to do something just because everyone else is happy and I have to join in to make you happy. What about me?

Today I can allow myself, today I can have a relationship because I can say what I want, I don't just do things to please the other person. Do I still have issues with masculinity? Of course, it's my process. And I'm discovering a lot more about myself. I always joke, "Oh, I never say 'I'll never do this.'" I always say that to myself, I'm a Gemini, I might drown in it, you know? (laughs)

Sometimes you feel stuck and don't know what to do. Some days I'm sad, some days I'm happy. Because that's life, you know? It's ups and downs. Life is made of highs and lows, and you learn from it. Learning to live in society, learning to respect each other. I learned so many things. I didn't even know what non-binary was until I was like, "Wow, maybe this fits me," you know, fits my body. Many trans people realize that just being trans doesn't fully encompass their bodies. Many non-binary people will eventually feel that just being non-binary doesn't fully encompass their bodies. It's a process, it's ongoing, it's evolution, it's being human. That's how it is. But there will always be someone justifying their prejudices, always someone thinking what the neighbor is doing is wrong, even though the neighbor isn't even talking to them, you know? But "that's wrong." People love playing Big Brother (laughs).

With my family, coming out was pretty smooth. I came out twice, first as a lesbian and then as trans. And my brother too. I think it was much easier for me to come out as trans than for my brother to come out as gay to my father. Because like I said, my brother is a Black man. Man, in Rio Grande do Sul, gay? What? No way. My mom already knew about my brother, that he was gay. But my mom didn't know I was a lesbian, nor did my dad. So when I came out as a lesbian, I came out to both of them. And then my brother took advantage of that open door and came out as gay to my dad. And for my dad, it was much easier, from what I saw, to see me as a lesbian, like, "Okay, Mô has always been like this," cool. But with my brother, it was super hard, super hard for him to accept it. I could see that. He just didn't understand. But I'm not crucifying my parents either. It's their cultural background, just like we have our own cultural backgrounds and questions, right? Something obviously didn't match what he thought for him to have that prejudice. And my dad was very religious, so he had to find his own answers. My dad and mom are Jehovah's Witnesses. My brother and I aren't anymore. But they still go to the congregation, and my dad can actually show you in the Bible that trans bodies are accepted, you know? He'll grab a Bible and show you, he'll say, "God loves all of us," you know? My mom will say the same thing. My dad reads the Bible daily. He's a very wise man, and my mom is too.

And it's that thing about knowledge, right? My parents only finished elementary school, but they have their own knowledge, the way they learned, their intelligence. They may not have finished high school, but they are very intelligent. My dad can assemble a machine, while an engineering graduate might not know how to. That's what I mean by knowledge—we shouldn't devalue it. Just because someone doesn't have formal schooling doesn't mean they're dumb. No. It's about valuing different types of knowledge.

So my parents are very intelligent and very loving as well. It was a difficult process for them, accepting my brother and me. It's still a process. To this day, my mom calls me by feminine pronouns. And my dad calls me by my old name and feminine pronouns sometimes when he slips up. Now they just call me "Mô," and I tell them, "Okay, it's time for you to start trying harder," you know? "Because if I keep allowing you to call me Mô and keep allowing you to get my pronouns wrong without correcting you, you'll keep doing it." If you don't point out that something is wrong, people will continue doing it because it's comfortable that way. I'm always correcting them, and they're getting much better at it. I'm always paying attention, trying to get them to use my name. It's a process for them too because they raised their little girl, and suddenly that little girl isn't a little girl anymore. But I've always been the human they raised, and the love they gave me... I've always been there, I've never died. I've always been the same person, just with a different experience—a trans experience.

They're very chill. They always say: "Dad loves you and your brother and will keep loving you." And they don't understand parents who kick their kids out of the house. They really can't comprehend that.

I hardly spend much time here in Novo Hamburgo; I'm always in Porto Alegre. But at the beginning of my transition, it sucked because, like, my city is German, right? There are many German descendants. In some neighborhoods, there are a lot more Black people, but those are the more distant areas where they push poor people, out of sight, you know? So here in this more central region, I think I'm the only Black person in the neighborhood—my family here. It's like, damn, everyone stares at you, you know? When I had my afro, wow, that was the first thing. When I started growing my hair out, the whole city stared at me. Even the Uber driver still recognizes me to this day (laughs). Like, I didn't even know who he was, and the first time I got in his car, he was like, "Man, I saw you walking around with that big afro, I thought it was so cool." Like, I was known in the streets, you know? And I had no idea who these people were. And yeah, it sucked. Sometimes you just want to buy bread without being noticed, but you can't go unnoticed because you're different to them. So sometimes it sucked, and sometimes I didn't care, you know? Sometimes I even liked it, thinking, "Yeah, go ahead and look, I'm awesome!" (laughs). So there were phases like that. But I didn't spend much of my transition here because I studied and worked in Porto Alegre, I only came home to sleep. And on weekends, I usually went out in Porto Alegre.

Being trans in Novo Hamburgo... When people saw me as a masculine lesbian, they already looked at me differently—"Is it a man or a woman? What's going on, my god?" I also had straight hair, so I stood out even more. And like I said, sometimes I was comfortable, and sometimes I was completely "damn, just stop staring at me, this sucks." And I think that contributed to my anxiety because I always felt people were looking at me. To this day, I don't like crowds; I prefer silence, just passing through quietly. I developed a fear of people back then, and I think part of it was feeling like everyone was always watching me because I knew I was different, even when maybe they weren’t even paying attention to me.

Now that I imagine I have more passing privilege, I don’t feel as uncomfortable because people don’t misgender me as often. I still feel insecure, of course, because I have a trans body, but since people sometimes read me as a cis guy... For a Black trans body, I became a threat, you know? Because I have a Black body, people think I’m going to rob them, while I’m the one who’s actually afraid of them. And that’s what happened—I became a threat. When, in reality, I’m the one being threatened. But with other guys, they treat me like a bro. Sometimes I don’t even know how to act, I feel pressured, like, "Can I say ‘excuse me’? If I say ‘excuse me,’ will he realize I’m trans and beat me up?" You know? I fear violent and prejudiced reactions, whether physical or verbal. Because it sucks—even if verbal violence isn’t physical, I’m a sensitive person, and it wrecks my mental state, you know? If I’m sad in that moment, it’s going to be really bad for me. And it’s not just because I’m sensitive—it’s because it’s violence.

At the beginning of my transition, when I had long hair, people read me more as a lesbian in masculine clothes. I loved my hair, like, a lot, but it started to bother me because people kept identifying me as a cis lesbian woman. I think it bothered me so much that I got tired of my hair and cut it off. And when I did, I felt better—I felt like I was being read more as a guy. And now I believe people see me as a guy, like a 19-year-old kid. I get in an Uber, and they go, "Hey, kid," "Wow, kid," "Bye, kid," you know? It’s so simple—someone just said "Bye, kid." But a few months ago, that could have been a nightmare, I could have faced violence. It’s the fear of people’s reactions.

And Porto Alegre is really oppressive. You go from having a Black woman’s body—a body that can be violated at any moment by a man if you’re in a dark street, you know? So many times, I’d rather pay for an Uber than walk, to avoid the risk. I’d walk faster, be mindful of the time, choose my clothes carefully. I always, always—until today—I walk with a lot of tension in Porto Alegre, because anything could happen. Besides getting robbed, someone might "discover I’m a girl" in that moment, because from a distance, they thought I was a guy, but then up close, they read me as a cis lesbian woman, and then, you know... In Porto Alegre, you have to be alert all the time, afraid of being attacked.

And when I became legible, to cis people, as a Black man, the shitty part came, too—I became a threat, you know? Now I have to be mindful of police cars because they could stop me at any moment. And if they do, what could happen to me? Because when I was read as a Black lesbian woman, I had the safety of "Oh, the cops won’t beat me up because I’m a woman." But now I’m a man. I can walk more safely alone at night, maybe not fear getting mugged by another guy because he sees me as one of his own, but I’m also completely seen as a threat. If I start running... I always take my documents with me if I go for a run. If I go anywhere, I always have to carry my documents—any small thing, I can’t even go to the corner store without them. And then, shit, I always have to be on guard.

Depending on the time of day, a police car slows down to look at you. And then you hear your friends sharing similar stories. I always try to be careful, to pay attention to where I am, where I’m going, and what I’m wearing. I’ve always done that. And Novo Hamburgo always demanded that because, as a Black person, you have to be careful about what you wear. Just because you’re Black, there are already so many things you have to do. If you’re buying a bottle of water, you’re not walking into the store without a shopping basket—you’re not crazy. You’re grabbing a basket, period. If you ask another Black man, he’ll say, "Yeah, obviously, I take a basket—otherwise, security will follow me right away," you know? Always. So a lot of these prejudices come from race. And then there’s race and gender combined. Depending on how they’re reading you—"Oh, it’s a woman, okay," "Oh, it’s a man, okay"—they’ll treat that body differently.

And as a trans man, yes, I’m still afraid of being raped. And one of the things I want to get back into is fighting, so I can feel safer in society. Against any kind of violence that could happen to me, to my body. Because I’m small—I’m a small Black guy—so if two bigger guys come at me, they could rob me, you know, and then maybe start touching me, thinking... I could be wearing a sports bra, or whatever... And as I gain passing privilege, I get, let’s say, a kind of "security"—people just go, "Oh, it’s a guy," you know? But from the moment I don’t know how they’re reading me—if they’re seeing me as trans or not—I don’t know what they’re perceiving in my body.

•

•

•

The future of gender will be multi-plural, I think. Gender used to mean just the female gender. "Gender studies" used to mean studying women. So that’s it—multi-plural. It’s going to be much broader. It’ll be like programming languages—we’ll have different languages, and you’ll use the one that fits you best (laughs).

•

•

•

A message? Love. Above all, love more. Listen. Above all, listen to people. Respect. And love. It might sound like some corny namasté phrase—"the world needs love"—but that’s exactly it. The world needs love, you know? The world needs love and respect. And to get to that love and respect, people have to step out of their privilege and use their privilege. Use your privilege to help build a better society, to improve it, you know? That’s it. If you’re white, you’re not going to experience racism, but your friends and others do. Use your privilege to fight against racism. Just because you’re white, just because you’re not Black, doesn’t mean you shouldn’t get involved. No. You should get involved. You should use your privileges to help dismantle this system, got it? That’s it. Use your privileges to make society better.

Allow yourself. You have to truly allow yourself. To experience another culture without prejudice. To understand the other. In that moment, you’ll start to grasp what it means to be a trans body—that people exist, and they just want to have their names respected. Curious? Click. Do it. Click, watch, come see. Come look. Come ask. Because people just assume things in whatever way they think makes sense, in search of answers. They’re curious. So ask. Without violence. Have emotional responsibility for others, you know? It’s not just in romantic relationships that we need emotional responsibility—we need it in everything. With society as a whole. Have that emotional responsibility. And allow yourself to learn about others. Stop making assumptions.

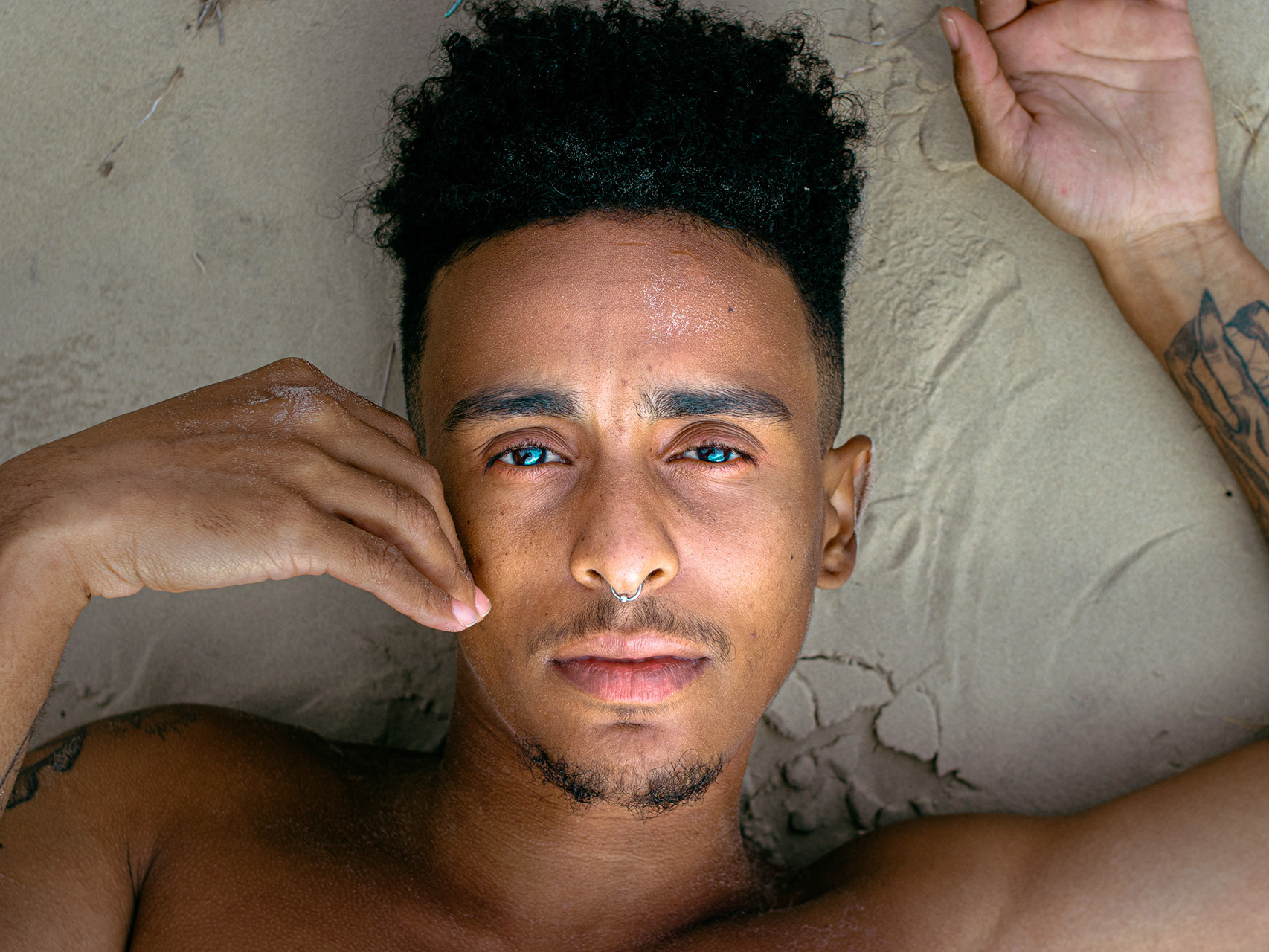

Morgan Lemes

1993

Graduating in History at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul. Professor of History in the collective TransENEM. Student in Computer Networks at the Federal Institute of Rio Grande do Sul. Screenwriter (beginner) and digital communicator.

1993

Graduating in History at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul. Professor of History in the collective TransENEM. Student in Computer Networks at the Federal Institute of Rio Grande do Sul. Screenwriter (beginner) and digital communicator.

Trans man, he/him pronouns.

7 months on HRT.

@morganlemes

*essay from February 2020, Novo Hamburgo (RS), Brazil.

-

ser trans portrays and creates space for trans, travesti, and non-binary people to be the protagonists of their own stories, rethinking a Brazilian trans archive.

A project conceived by Gabz 404.

SUPPORT THIS WORK