[fotografia analógica - dig/scan lab:lab]

Gabz: Would you introduce yourself?

My name is Ayana Kai Drakos, I'm 33 years old. I am mixed-race. My gender identity is trans, non-binary and I use they/them pronouns. I grew up in Portland, OR, USA, where I live. I lived in Tacoma, Washington after high school and then lived in Madison, Wisconsin for graduate school and then moved back here in 2017.

In college and in graduate school, I studied History and African-American studies, and I still am finishing my PhD in History. My focus for my PhD is on black, queer and feminist healing practices, specifically related to working with and reclaiming relationship with the land as a site of healing. Along with that academic work, I also have been working as an apprentice and learning organic farming, growing vegetables as well as plants to make medicines. I've been on a journey to be a medicine person in that realm, with an interest in integrating my academic work with more community engagement work. I would love to be able to provide medicine to my community, to other QTBIPOC people who might not otherwise have access to these kinds of medicines. And I have a dream of somehow combining it all into some kind of education for youth, like a school that is rooted in community and with the land and with Earth.

G: Would you willing to share a bit about your gender journey?

Lately I've been in the process of going back and looking at photographs of myself when I was a kid. To integrate my gender and have more of an understanding of my gender journey and to do some of my own healing work around the child parts of me who weren't able to be nurtured as a young trans being, because there wasn't language for that – for transness at the time when I was growing up – and I wasn't really surrounded by any other trans or queer people. And so, you know, the language that was used about me or I might have said about myself as a child was a tomboy. I would say that was my gender identity as a kid, because that was the word I had. And then I went through various stages as a young adult of trying to fit in as a girl. That didn't last very long, but there were a few years where I tried to be a girl (laughs) that was awkward.

I feel like since leaving home, like since high school - I was a jock. And so you could kind of get away with wearing sports clothes and be a girl and nobody would really say too much, you know, 'cuz you're a jock. I've been in a process since then of coming more and more into myself as non-binary. When I was younger, there was still such a binary within queerness, like a pressure to fit in within an idea of one or the other. And so I remember also being uncomfortable with that, but not having language for it... In the last ten years or so, I feel it's been a process of really reclaiming and claiming non-binary-ness and what that means for me and feeling more comfortable within fluidity. Which has been fun and liberating.

G: You were saying you didn't have language before. So I was wondering: how did you find this language?

I think finding language comes from within queer community – as our language has evolved over time, with trans folks in particular leading the way, breaking open binary language. It comes from the young people. I feel like it reached me later in my twenties, being around younger queer people and witnessing how they were fucking with all of it. And then it's almost like I feel like, you know, we who were a little bit older got to benefit from some of the work that they were doing. And I even remember at a time when more and more people were identifying with they/them pronouns, it feeling, even for me, kind of strange or like I didn't really understand. And then slowly over time feeling more and more in my body, trying it on, like, oh yeah, that really resonates. And so it wasn't always. All of our brains have to be de-conditioned, right? It's not just hetero, straight people who have been changing through this process or need to change through this process. I think it's also within queerness that we've evolved and changed as all of us feel more and more into what liberation means.

♪ Anita Baker, "Body and Soul"

G: You mentioned that you work a lot with the land, and have a dream to help queer and trans people who don't have access to this healing. You study history, but you are also in contact with nature and plants. So there are these connections to land. How do you think this can be a healing process, both for you and for other trans people and people of color?

From a historical perspective, the first thing that comes to mind, especially for those of us of African descent in the so called United States, is that the root of so much of our trauma is connected to having been disconnected from the land and from our lineages, our healing lineages, our ways of living and being with spirit and with the food we eat and with taking care of ourselves. This is at the root for me of how healing has to happen - through reconnecting and reclaiming what has been taken. And that looks different for different ones of us. Depending on where our ancestors are from and what our practices were. And I think a lot of people right now are in a moment of going back. And this connects to the memory piece of, first, who are our people? For many of us, we don't know. And so we have to get quiet enough to listen for them.

If you’re black in the US, oftentimes the traditional methods of finding that out through things like records or archives don't exist. So it really becomes a spiritual practice of discovery.. for me, I can hear most clearly in that way when I'm in nature, when I'm connected to the soil and my body is on the ground. It's like a trust process and a faith process which is also decolonizing, you know, to remember our intuition and to practice listening to ourselves and trusting ourselves as queer people, as trans people, as BIPOC people. That, you know, is everything we've been taught not to listen to, not to believe is valuable, where not to receive knowledge from. So that practice in general of getting quiet and being outside and listening feels liberating to me and healing for those reasons. And that can be traced all the way to growing plants or food, to the seeds themselves. More increasingly, on a survival level, we're going to need to relearn how to grow our own seeds and grow our own food because the last few years in particular have shown us we can't rely on any other system to do that for us. There's really cool work happening right now around seed saving and reclaiming heirloom seeds or seeds that have been passed down through different cultures and lineages to keep those alive and keep growing them - to get them to the communities from which they came or from where they were taken.

That's one thing that comes to mind. For me personally, I became very sick with a mysterious illness called Lyme disease, in 2017. It redirected the course of my life and from that place of illness and my body really having to, like, really it felt like a spiritual and embodied illness in the sense that one of the things that came through during that time was that I had to learn how to live differently if I wanted to be in this world. And part of that was very clear, was that I had to get back to the land and trees in particular. I started getting all these images of trees that had taken care of me over the course of my life when I was a little kid. And it felt like I was being asked to return to those trees and give them gratitude and really see them and cultivate a relationship of reciprocity. And it's from that moment… that's where I keep coming back to.

G: How do you feel the connection of what you are speaking of with your gender journey? Because it kind of happens at the same time.

Nature is so queer, you know what I mean? Like, it's so fun to just go into the forest and observe the shapes and the weirdness and the perfection in every expression of life being itself. That's what transness and queerness is. An invitation to show up as we are, stripped away from all of the bullshit of the things that we're all told we're supposed to be. That’s so fucking beautiful.

So, it feels inherently connected to me. Because that's what it feels like nature is asking of us. That's what it feels like. The plants, the water, all the elements, you know, just to be in our wildness, you know what I mean? So the more that I feel like I observe and just listen to all the shapes and the textures – it's also sensual and sexy and also not linear, there's no one mode – the more I feel like I'm able to be myself. And then there’s mycelium… lately I've been getting to know the mushrooms more and the feeling of their interconnection and reliance on each other. We have so much to learn from how nature takes care of itself. For us, we know this, that our survival is dependent on us caring for each other because systems haven't cared for us. And so there's also this very queer care network that I feel becomes clearer and clearer the more we listen to the mushrooms.

G: I love that you brought it up the care for each other, because I think it's very unique, not just for queer people, but for groups that have been marginalized throughout history and have had to build their own communities. I'd like to ask you what it's like to be a trans person in Portland, but I also want to know more about the importance of your community. How do you think you are being cared for? Do you feel this goes against the norms somehow?

I've benefited from so much generosity and there's a way that part of my healing journey I can feel has to do with breaking through really deep family and ancestral patterns of isolation. And I think part of my own survival mechanisms for being trans for a lot of my life without a lot of support for it was to isolate. And so part of my own healing journey has been to break through that. It is also connected to that moment of illness that I talked about because I was pushed to a place where I had to receive. I had to open myself through receiving care from people because part of what happens with an isolation pattern is that you can tell yourself that people don't care about you or don't love you, etc.. Or you know, a lot of that is fear, like, "I don't want to be too much" because we're all told we're too much. And so that was a really big moment for me when I let people know what was going on, to say, "I'm really sick". People showed up for me in a way that my heart just had to open. It was like a softening process and I couldn't even believe it. People are so generous. When you let them be, you know, people are so loving and caring. I received so much nourishing food medicine. Since then, and also since leaving the place where I was in school, which is an inherently isolating kind of environment, and coming back home and really focusing on reconnecting with the land where I'm from and my family and building community here I continue to be met with that feeling of just wanting to be in community in a way that feels generous. I want to give freely and receive freely. That also feels against the norm of individualism or capitalism, where we're taught that success is to have all these things or have this certain status or income when really, to me, success is measured by the wellness of your community, and how well we take care of each other. How well do people feel taken care of? That is all that really matters. And I also feel that the more we're in reciprocity and care with the land as a practice and then in community with other people who are practicing that, you know, it can be such a self-generating generosity…there's abundance in that.

G: After the photos, I remember you saying a lot of nice things about this process, could you comment a little about how the rehearsal was for you?

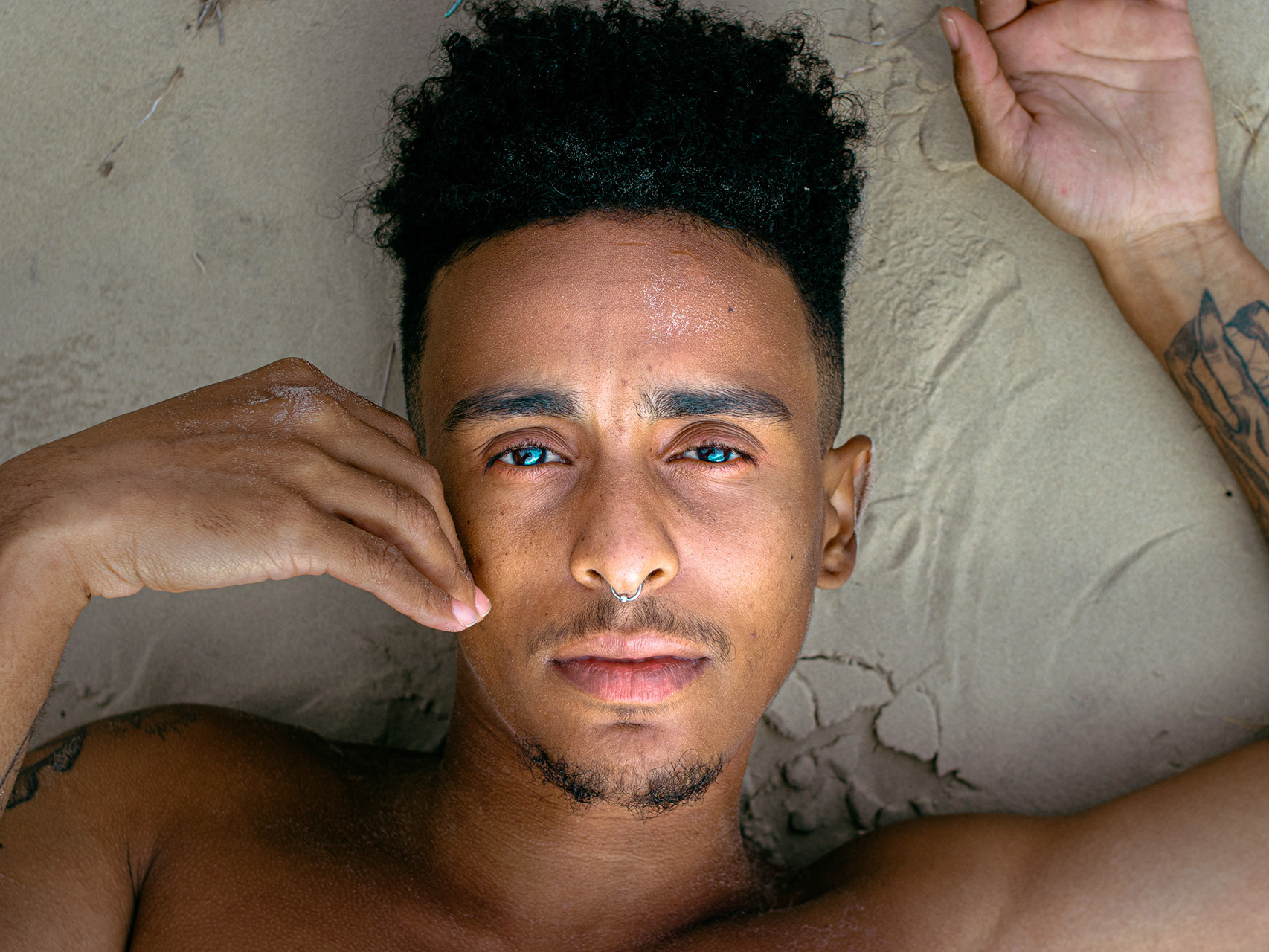

First, it was just so fun and freeing and creative. The feeling I felt in our photo shoot I don't think I'd ever felt before. And a lot of that has to do with you and who you are and the space that you hold and create and how safe I felt with you to be very expressive. And the timing, you know? I felt like I was going through some acute heartbreak and heartbreak can also be very opening. I was working with a lot of big feelings that were able to come through in the shapes my body wanted to make. The process felt like an empowering way to be with myself and to be with my emotions and to actually move through some of them and feel them with more agency. Our photoshoot felt very fluid in the way that I feel very fluid. It felt like I could be big, I could be small, I could be submissive, I could be more dominant. I could hold myself. I could be alluring or seductive. I could be inviting someone in. I could be looking away. I could be staring straight at what's there, staring straight at you or, you know, it felt like I could embody so many different ways of being, in your gaze. It felt incredible.

G: I don't even know what to say, I wanted to give you a hug right now. I really love that we did a photo of us where I was photographing you. I love that we somehow captured this moment. Is there anything else you think is important to share?

I want to express gratitude to you and to this project. And I don't even know all that makes this project possible, but participating with it has offered me something that I didn't know that I needed. And we spoke in this conversation about care and the importance of community care and being seen in this way and giving space to express feels like a really important form of care. And I can feel the way that the photoshoot and just the process of this conversation is offering space to a part of me that didn't know I needed that space or it just feels like care and I hope it continues to be supported so more people can have this feeling.

.

.

.

Ayanna Kai Drakos

born year.

Bio

gender id

pronouns

@ig

born year.

Bio

gender id

pronouns

@ig

hrt time

*essay from June 2022, Portland (OR) - USA

-

This project was idealized and is made by Gabz, a trans non-binary multiple-language artist. ser trans is a project that portrays and also makes room for trans, travestis and non-binary people to be the protagonists of their own stories. We are seeking for representation in front and behind cameras. This project started out of urgency. Ser Trans is made also in collaboration with Lau Graef, transmasculine artist, visual arts student and autonomous activist; Luka Machado, travesti, actress, visual artist and activist; and Morgan Lemes, black trans man, screenwriter, researcher and photography assistant.

ser trans is autonomously produced by trans people and all content is offered for free. You can help sustain this project by sharing it with friends and making a one time or recurrent donation - any value is welcome. Thank you for supporting a project made by trans people <3

Gabz self portrait, dev by Eloá Souto